(Un) Huggy Bunch

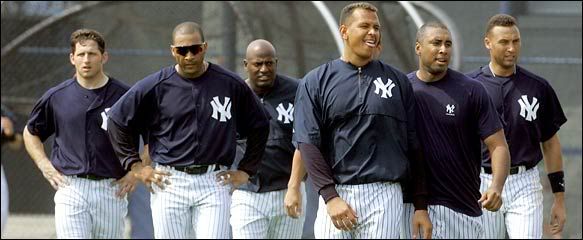

Cold professionalism or...

...happy good times? You be the judge.

The New York Times has an article by Benedict Carey today entitled “Close Doesn’t Always Count in Winning Games.” Carey writes, among other things, of the Yankees’ clubhouse and the aloof nature of the players on the team. He compares them to

Carey writes: Yet at the eye of this hurricane, the clubhouse feels as sleepy as a back porch on an empty afternoon. This is not a team on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Nor is it one that - like its archrival, the world champion

But social scientists who have studied group performance under pressure say that often it is decentralized groups (like the Yankees) that prove more resilient than strongly connected ones (like the Red Sox); they are better able to weather outside criticism and internal quarrels.

So, basically, the Yankees hate fun. And that’s good. Forgive me for oversimplifying but don’t these millionaires play a game for a living? Shouldn’t it, maybe, I don’t know, be fun? I suppose they don’t need to love each other and be putting Ben Gay in the newbies’ jock straps but, I mean, they could smile a bit, no? But okay, if you say this works then I’ll listen. Please continue.

Evidence from personality profiles and from studies of military, corporate and space flight crews suggests that looser ties between group members can be a strength, if the team includes individuals who can generate collective emotion when needed. And the Yankees have several of them.

“Individuals who can generate collective emotion when needed?” So the Yankees employ androids? Because that sounds awful robot-y to me. I don’t know how much I understand this “generating emotion” thing. I’ve always thought that emotions, by their very nature, are often uncontrollable and as such, just kind of happen, for better or for worse. Example: when Manny Ramirez is so overcome by joy that he sprints out to left field carrying a tiny American flag symbolizing his new status as an American citizen and he can’t keep the grin from cracking his face, that is good emotion. When David Ortiz gets so upset with an umpires balls and strikes calls that he throws bats out of the dugout and very nearly hits said umpire, that is bad emotion. But the point remains: emotions are a very real part of baseball and genuine emotion is important. I’m not sure you can turn it on and off like that. And even if you can, if your teammates aren’t all that close to you, how do you expect to be able to inspire them with your displays of “emotion?” Just wondering.

Carey goes on to write:

In interviews during the first week of spring training, Yankees players said there was no single dominant personality in the clubhouse, no boisterous leader. The diffuse nature of the group seemed evident. The team's stars have corner lockers, or lockers next to open spaces, and a few of them are centers of gravity. In one corner, pitcher Mike Mussina anchors a group of pitchers and other players. In the opposite corner, outfielder Gary Sheffield centers another small group. And in a third corner, catchers Jorge Posada and John Flaherty sit. A clutch of Spanish-speaking players occupy a bank of lockers in the center of the room. Shortstop Derek Jeter, the team's captain, made the rounds of the clubhouse on his first day, then settled at his locker like any other teammate: hardly a portrait of the take-charge leader many imagine.

"You could be a fly on the wall in the clubhouse all season long, and if you didn't know already, you couldn't even tell who the leaders of this team are," Flaherty said.

I’m still unclear if this is a good thing. I understand that you don’t necessarily want a pampered super star hogging the spotlight and making himself a lightning rod for criticism as well as praise but explain to me exactly how it’s good for the team for everyone to have to fend for themselves with no back up from their teammates? Explain to me why it’s a positive thing that no one came to A-Rod or Giambi’s defense during the recent rash of accusations and barbs. I understand the need for players to be accountable for their actions but don’t you eventually reach a point where you want to turn to your teammates for at least moral support? I would think it would be somewhat divisive if you see them off in the corner, counting their endorsements and ignoring you and your plight.

Winning is more likely to create team unity than vice versa, Torre has said repeatedly, and the evidence backs him up, said Dr. Richard Moreland, a professor of psychology and management at the University of Pittsburgh. Team cohesion is a hard thing to measure in the first place, Dr. Moreland said, and dozens of studies of sports teams find that, although having players who feel team unity helps performance, "it is not a strong effect, compared to the effect of performance on cohesion."

This is a very tenuous chicken or the egg argument, I think. Does winning make teams closer or does cohesion lead to more wins. I’m not sure there’s a right answer and this is the one area where comparing the Yankees and the Red Sox really won’t do any good because regardless of the standings, both teams win an awful lot of baseball games. It’d be interesting to see the effect of clubhouse chemistry or winning (or lack thereof) on a team like the Devil Rays or the

On a tightly knit team, by contrast, a falling out between key members can divide a squad, forcing people to take sides, psychologists say. "The idea is that any sort of problem is likely to ripple more strongly and quickly through a close group than one with weak ties," said Dr. Mark Granovetter, a professor of sociology at Stanford.

Perhaps, but if that’s the case then one could reasonably assume that happiness and joy, not to mention Big Papi’s Cheshire smile would be equally infectious.

Psychologists who have studied the personality profiles of people who face far greater pressures than winning in October - including special-operations forces and astronauts - agree that those who do well share distinct qualities: they tend to be independent, confident, able to tolerate uncertainty and socialize easily with others.

It seems that Mr. Carey has hit upon the problem with his hypothesis in this paragraph. “People who face far greater pressures than winning in October.” Exactly. You can study as many Navy Seals or Fortune 500 entrepreneurs or cardiologists as you want, but in the end, these men that you’re talking about play baseball. They play a little boys’ game. And they get paid millions of dollars to do so. Yes, there is pressure, but it’s baseball. I cannot stress enough how important it is to differentiate between the pressure of October baseball and the pressure that people involved in something like Doctors without Borders face every day. It’s not the same thing. It may seem that way to us, and heaven knows I am eternally guilty of living and dying by the game of baseball, but in the end? It. Is. A. Game. I tend to think that it’s the players that can recognize that and enjoy this amazing opportunity with which they’ve been blessed, that can perform the best.

"But they are not too outgoing, not socially needy, not the sort of people who need others for support," said Dr. Lawrence Palinkas, an anthropologist at the University of California, San Diego, and the chief adviser to the National Space Biomedical Research Institute, which studies spaceflight.

That’s kind of too bad since, despite it’s individual match ups, baseball is still a team sport. I remember Mike Mussina complaining that all he could do was pitch. He couldn’t score runs. If his teammates are not particularly close to him – and all reports indicate that they are not – how are they going to feel being called out by their pitcher? Will that make them want to score runs for him? I don’t know. But I do know that if they get along and genuinely care for each other, ballplayers will be more likely to help each other and pick each other up when they’re struggling. That’s a fact of human nature.

And no researcher can predict at that point which system will prevail, the centralized passion of the Red Sox or the diffuse professionalism of the Yankees.

One thing is certain for the Yankees, though: if they fail, they will face another off-season of hearing how soulless they are compared with

That may be the only solid truism in Carey’s article. What he neglects to mention, and what I see of utmost importance in this argument, is how a team of “diffused professionals” will be viewed by the fans, especially when compared to a “band of brothers.” Obviously, I’m a Red Sox fan so it’s pretty difficult for me to remain impassive or to understand how the Yankee way of doing things would seem appealing to anyone. But you have to wonder, don’t you want to follow a team that has fun? That clearly enjoys playing baseball? That likes each other and the fans and that takes the field with a smile?

Here’s the thing: as fans, most of us would give anything to be able to play baseball for a living. Regardless of age, rage, gender or athletic ability, there is an inherent envy we hold for our favorite athletes. We understand that, at times, things aren’t always, as David Ortiz says, “sunshine and beautiful things,” but that largely, it’s a good life. And so we appreciate those players that seem to understand how lucky they are. We applaud guys who take the field smiling and who seem to genuinely enjoy themselves. We don’t want a group of sour-faced pusses looking like they’re about to sit down for a nine-hour TPS report meeting. We want our players to have a good time. Because then we, transitively have a good time.

The bottom line is that baseball is a game. And it should be fun. There are ups and downs, as there are with anything, but games should be fun. That’s why they call it “playing” and not “working.” I am mostly too young to vividly remember the days of “25 players and 25 cabs” but the team I follow now is vastly different than the Yankee squad. It’s not just the hair or the baggy uniforms or the general messiness of the team, those are just the most visually apparent differences. It’s the warmth and the love that these guys have for each other. I once heard the Yankees referred to as the “Stepford Team” and that seemed remarkably apt. They are sleek, shiny superstars, cold and perfect. Like robots. And while that may win them a lot of games and it may even earn them some more championships, it won’t make a true fan smile. After all, you can’t hug a robot.

<< Home